Author Archive: Ginger

Restorative Retreat for Recovery Coaches on y our Xmas List!

Put this on the top of your Christmas Wish List!

How awesome would it be to have a self-care day packaged and ready to go at your fingertips? Here’s your chance! Join Liz Seaman at the beautiful, sprawling Hallelujah Farm nestled in the small country town of Chester- field, NH for a day of yoga, meditation, acupuncture and fellowship. The day will also include reflective journaling, other bonding activities and a wholesome lunch.

Total cost is $70 with a $30 deposit required to hold your space on or before January 4th. Checks can be sent to Cornerstone Yoga – 815 Court St. Keene, NH 03431 – Register HERE

About the Instructor:

Liz Seaman has been leading restorative retreats for 10 years, both locally, in the Southwest, Maine and Costa Rica. She brings her warmth and humor to her teaching and excels at meeting people where they are. She is a long time yoga teacher and massage therapist. She currently works as a CRSW in the Monadnock area, as well as co-owns Cornerstone Center for Wellness in Keene, NH with her husband.

Questions Arise Over Profession Spawned by Opioid Epidemic

As he emerged from the grip of addiction three years ago, Derek saw how complicated recovery would be: programs to navigate, calls to make, forms to fill out, court dates to attend. All that on top of the emotional and physical strain of parting with the heroin and alcohol that had ruled his life for a dozen years.

But the 32-year-old counts himself lucky to have had a “recovery coach” guiding him on his journey from treatment to sobriety. The coach, Katie O’Leary, offered a deep understanding, and a motivating example of success: She started her own recovery from heroin addiction seven years ago.

O’Leary, who works for the North Suffolk Mental Health Association, belongs to a new profession whose role is expanding amid the opioid crisis. But as the use of recovery coaches grows, so do the questions: Who are they exactly? What qualifies them to do this work? What are the boundaries of their practice?

Governor Charlie Baker is the latest to seek answers, with his recent proposal for a commission to look into credentialing recovery coaches, a move that could lead to insurance reimbursement.

For Derek, who asked that his last name be kept confidential in keeping with the customs of Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous, O’Leary’s help made all the difference.

She told him where to apply for benefits, drove him to his first post-treatment sober house, stayed until he was comfortable there, and took his middle-of-the-night phone calls when worries kept him awake. Today, living in a sober house and working full-time, Derek meets with her about once every two weeks.

“When you start to get nervous, you start to fall, the recovery coach is the person who puts their hand out to you,” he said.

For her part, O’Leary, 37, understands the appeal of peer support. “If a clinician told me I have to do something, I would laugh at them and do the exact opposite,” she said. But suggestions carry more weight when they come “from somebody that has the same experience and the same pain.”

As he emerged from the grip of addiction three years ago, Derek saw how complicated recovery would be: programs to navigate, calls to make, forms to fill out, court dates to attend. All that on top of the emotional and physical strain of parting with the heroin and alcohol that had ruled his life for a dozen years.

But the 32-year-old counts himself lucky to have had a “recovery coach” guiding him on his journey from treatment to sobriety. The coach, Katie O’Leary, offered a deep understanding, and a motivating example of success: She started her own recovery from heroin addiction seven years ago.

O’Leary, who works for the North Suffolk Mental Health Association, belongs to a new profession whose role is expanding amid the opioid crisis. But as the use of recovery coaches grows, so do the questions: Who are they exactly? What qualifies them to do this work? What are the boundaries of their practice?

Governor Charlie Baker is the latest to seek answers, with his recent proposal for a commission to look into credentialing recovery coaches, a move that could lead to insurance reimbursement.

For Derek, who asked that his last name be kept confidential in keeping with the customs of Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous, O’Leary’s help made all the difference.

She told him where to apply for benefits, drove him to his first post-treatment sober house, stayed until he was comfortable there, and took his middle-of-the-night phone calls when worries kept him awake. Today, living in a sober house and working full-time, Derek meets with her about once every two weeks.

“When you start to get nervous, you start to fall, the recovery coach is the person who puts their hand out to you,” he said.

For her part, O’Leary, 37, understands the appeal of peer support. “If a clinician told me I have to do something, I would laugh at them and do the exact opposite,” she said. But suggestions carry more weight when they come “from somebody that has the same experience and the same pain.”

Recovery coaches, or “peer support specialists,” have been around for decades, originally as volunteers who had beat addiction and wanted to help others do the same. In recent years, hospitals, treatment centers, municipalities, and courts have started to pay for their services.

They are seen as peers able to guide and mentor, encouraging people to enter treatment or helping them keep on track in recovery. Usually they are not supposed to provide treatment, and most do not have advanced degrees. But there are no firm statewide rules — and insurance companies do not reimburse for peer recovery services, requiring programs that hire recovery coaches to find other sources of funding. No one even knows how many people call themselves recovery coaches, in Massachusetts or nationwide.

Kristoph Pydynkowski, director of recovery management at the Gosnold treatment center on Cape Cod, welcomes the governor’s proposal to credential recovery coaches, part of a wide-ranging plan to battle opioid addiction.

“It’s a like the Wild West,” he said. “We do need to come up with some standards and best practices.”

Pydynkowski got his start a decade ago while working as a dishwasher at Gosnold, newly in recovery after a 10-year struggle with heroin. Someone pulled him away from the dishes with a request to talk with a difficult young patient. With his Mohawk haircut and tattooed face, Pydynkowski sat down with the young man — and connected in a way that changed the patient’s life, and Pydynkowski’s.

Gosnold started its peer recovery program in 2012, and now employs 10 recovery coaches to help patients after they leave treatment.

Training and supervision are critical for recovery coaches, Pydynkowski said. “I’ve seen so many people do harm to themselves and others,” he said.

People whose own recovery is too recent can end up getting high with their clients, Pydynkowski said. Some, he said, work around the clock and burn out, endangering their own recovery.

Recognizing the need for education and standards, the state Department of Public Health began offering a one-week Recovery Coach Academy several years ago, and more than 1,000 people have completed the course.

In 2016, the department established a more rigorous program to certify recovery coaches. Applicants must take the one-week course plus additional hours of training in ethics, cultural competency, and motivational interviewing. Then they must complete 500 hours of supervised work as a coach. Starting in June, they will also have to pass an exam.

There is no legal requirement for recovery coaches to become certified, but employers are starting to send their coaches through the program, and may require certification in the future. So far, 16 people have been certified, including several from Gosnold and the North Suffolk Mental Health Association.

But the state has no official definition specifying what recovery coaches can and cannot do — one of the issues that Baker’s commission might address.

More than 20 states have some kind of peer recovery designation or regulation, and most New England states offer certification. But the requirements vary, and there is no national standard.

“We need to unify this discipline, and we need to put together some standards that are national,” said Cynthia Moreno Tuohy, executive director of NAADAC, the Association for Addiction Professionals. In January, the association plans to launch a national credentialing program for “recovery support specialists,” another term for recovery coaches.

The addiction professionals’ group has also worked with the American Professional Agency, a liability insurer, to offer malpractice insurance for recovery support specialists who become credentialed through its program.

One of the top concerns is defining the scope of practice, to ensure that recovery coaches don’t veer into providing treatment and do not try to replace trained addiction clinicians, Moreno Tuohy said.

Do recovery coaches make a difference? Data from Gosnold show that its clients maintain sobriety longer and have fewer admissions to hospitals or addiction treatment centers than before they enrolled in the recovery program.

A review of the research on peer recovery published last year in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment found the research very limited, but the few good studies suggest that peer recovery services “make a positive contribution to substance use outcomes.”

The North Suffolk Mental Health Association, where O’Leary works, employs five full-time recovery coaches, paid $31,000 to $35,000 a year, and two supervising coaches, who make $42,000 to $45,000.

It’s a challenging program to manage financially, because insurance companies do not reimburse for recovery coaches as they do for licensed clinicians, said Kim Hanton, the agency’s director of addiction services. Hanton arranges to cover coaches’ salaries through grants and contracts.

Coaches have a special touch when engaging people, including those who may not want treatment. “It’s like magic,” Hanton said. “You see sparkle when you see coaches with individuals.”

While she wants to protect the integrity of the profession, Hanton hopes that credentialing will not make the job too professional. Requirements for college degrees, for example, would cause her to lose some of her best coaches.

“I don’t want them to take away the magic in what they do,” Hanton said.

Felice J. Freyer can be reached at felice.freyer@globe.com. Follow her on Twitter @felicejfreyer

Online Motivational Interview Training

Hi All,

If you’re interested in taking a Motivational Interviewing training, here’s one you can take in the privacy of your own home, and probably return to it if you have questions (I don’t know this – just surmising); https://www.eventbrite.com/e/4-week-online-course-applications-of-motivational-interviewing-in-behavioral-health-treatment-tickets-39226787377

If you take it, please share your feedback with me at gingerross23@gmail.com.

Healthy choices today!

Ginger

Journal Writing Prompts for Depression & Anxiety

Here you go friends; this may be helpful to those who have a mental health condition as well as substance use:

What is a Recovery Coach by Malden Overcoming Addiction

Thank you MOA, for all you do!

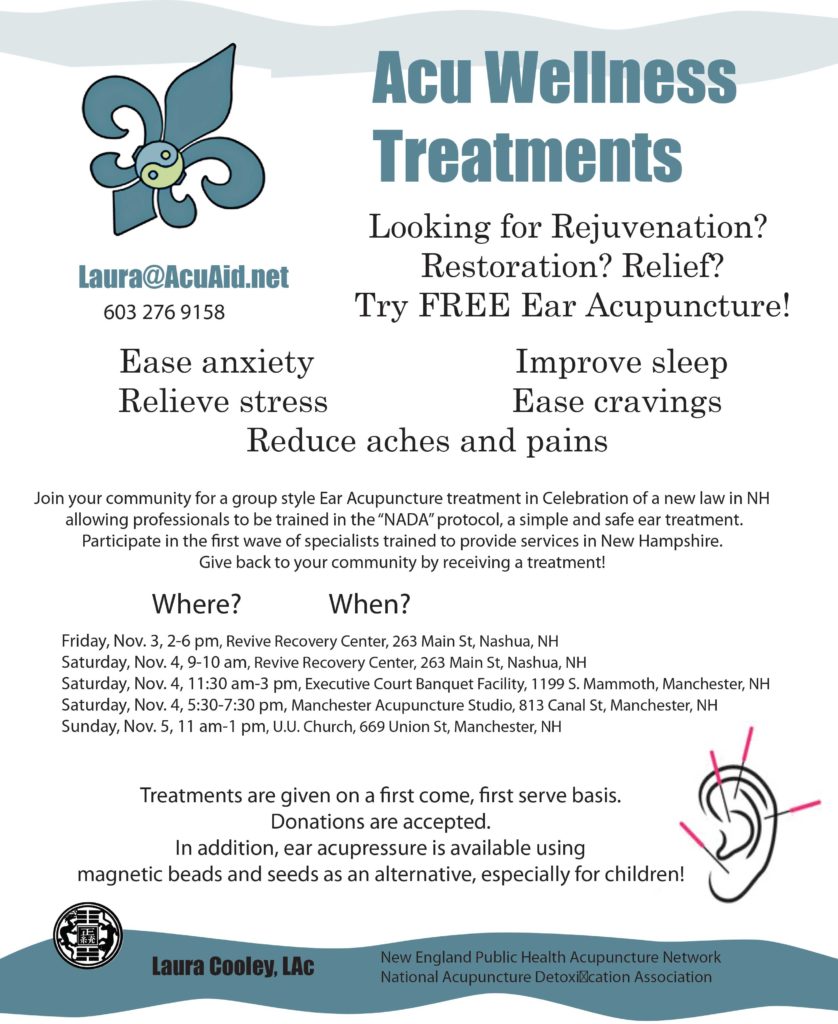

Accupuncture & Detox

FreeAccupuncture Downloadable Flyer! Take advantage, educate yourself, help others.

President Declares Opioid Crisis a Public Health Emergency

Tym Rourke and the NH Union Leader respond to the President’s declaration last week:

NH speaks: How to win the opioid fight

By SHAWNE K. WICKHAM

New Hampshire Sunday News

October 28. 2017 11:47PM

There’s been a lot of national attention on the opioid crisis, culminating in the President’s declaration last week of a national public health emergency. And that may mean more funding is coming to New Hampshire.

But where should that money go? What’s the fix?

We asked folks who have been on the front lines of the epidemic here for years for solutions. Here’s what they offered.

‘Unfettered access’

Tym Rourke (left) has chaired the Governor’s Commission on Alcohol & Drug Abuse Prevention, Intervention and Treatment for eight years. He said he hopes the President’s declaration will bring more flexibility and funding to the table.

Tym Rourke (left) has chaired the Governor’s Commission on Alcohol & Drug Abuse Prevention, Intervention and Treatment for eight years. He said he hopes the President’s declaration will bring more flexibility and funding to the table.

“Regardless of what part of the continuum you want to think about – more prevention, more treatment, more recovery – it’s about making sure that any individual has immediate, unfettered access to the things they need,” he said.

However, Rourke said, “None of this matters unless we can finally as a nation approach this disease just like we approach every other one. And the way we do that is people have insurance cards and they work.”

If people can’t access services, nothing will change, Rourke said. “Quite frankly, addiction (treatment) should not be paid for by grant,” he said.

Recovery housing

Bryan Patriquin (left, showing his tattoos that read, “To thine own self be true”), 27, of Manchester has been in recovery from heroin addiction for nearly six years. A senior at Southern New Hampshire University, he has his own business and plans to pursue graduate school in clinical mental health counseling.

Bryan Patriquin (left, showing his tattoos that read, “To thine own self be true”), 27, of Manchester has been in recovery from heroin addiction for nearly six years. A senior at Southern New Hampshire University, he has his own business and plans to pursue graduate school in clinical mental health counseling.

Patriquin says the greatest need for those new to recovery is safe housing. “When an individual gets out of treatment, very rarely does that person have a job waiting for them. Very rarely does that person have loved ones that are happy to see them,” he said. “Where does that individual go?”

Too often, he said, they end up back in their old environments and fall back into addiction.

Investing in recovery housing doesn’t get a lot of attention, Patriquin said. “But it’s going to save lives.”

Susan Markievitz (left) of Windham lost her 25-year-old son Chad to an overdose in 2014; she has another son in recovery. She now runs a support group for parents like her in Derry.

Susan Markievitz (left) of Windham lost her 25-year-old son Chad to an overdose in 2014; she has another son in recovery. She now runs a support group for parents like her in Derry.

If she had the ear of the President, she’d urge him to fund sober living programs that offer education and job search skills to help people get back on their feet after treatment. “Not only are they fighting their addiction, but their minds are also swirling: ‘Where am I going to get a job? How can I work?'”

Full-service recovery

Donna Marston (left) became an unwilling expert on opioid addiction when her son became addicted. Since then, she’s created support groups for parents, written two books about her family’s journey, and started a scholarship program to help those in recovery with expenses. She also hosts an online support group that draws members from all over the country.

Donna Marston (left) became an unwilling expert on opioid addiction when her son became addicted. Since then, she’s created support groups for parents, written two books about her family’s journey, and started a scholarship program to help those in recovery with expenses. She also hosts an online support group that draws members from all over the country.

Marston said if she had a million dollars, she would build a full-service campus to bring people through detox, inpatient treatment and recovery. “The program would fill in the gaps that people often fall through when they are in early recovery such as day care, transportation, how to live a life without drama, chaos and lying,” she said.

It also would provide parents and other family members support services.

Insurance coverage

Sarah Freeman (left) is executive director of New Hampshire Providers Association, which represents prevention, treatment and recovery providers. She said in the view of providers, two of the biggest barriers are financial uncertainty and workforce shortages.

Sarah Freeman (left) is executive director of New Hampshire Providers Association, which represents prevention, treatment and recovery providers. She said in the view of providers, two of the biggest barriers are financial uncertainty and workforce shortages.

She said it’s difficult for providers to expand services when they don’t know if programs such as Medicaid expansion will even be there; it’s currently due to sunset at the end of 2018. “If we’re not going to have a way to pay providers who treat those folks, there’s no safety net,” she said.

Michele Merritt (left), senior vice president and policy director at New Futures, said making sure that Medicaid and private insurance cover treatment and recovery is critical. “If we’re going to make a dent in the opioid crisis, the things we should be doing are ensuring that people have access to affordable health coverage, and once they have that coverage, that they can actually use it.”

Michele Merritt (left), senior vice president and policy director at New Futures, said making sure that Medicaid and private insurance cover treatment and recovery is critical. “If we’re going to make a dent in the opioid crisis, the things we should be doing are ensuring that people have access to affordable health coverage, and once they have that coverage, that they can actually use it.”

Merritt said New Hampshire has been able to increase investment in recovery support services and prevention only because Medicaid expansion covers the cost of treatment for thousands of state residents.

Mentor the youth

Laconia Police Chief Matthew Canfield (left) says it will take a multi-pronged approach to address the crisis, including treatment, law enforcement and drug courts.

Laconia Police Chief Matthew Canfield (left) says it will take a multi-pronged approach to address the crisis, including treatment, law enforcement and drug courts.

But Canfield said what’s often overlooked is prevention.

His idea is to have police officers serve as mentors to middle-school students, and have students do their own research about the devastating effects of drugs and then teach their peers.

“Because once somebody is addicted to heroin, it takes such a strong hold on them,” he said. “Even if they get treatment and they become sober, it’s a lifelong struggle.

“So let’s put more time and effort and resources into prevention before people have the opportunity to try this stuff,” he said.

Cut the strings

Melissa Crews (left) serves on the board of Hope for New Hampshire Recovery. A successful business owner, she’s been in recovery for 24 years.

Melissa Crews (left) serves on the board of Hope for New Hampshire Recovery. A successful business owner, she’s been in recovery for 24 years.

She wants to see more funding for accredited peer support programs “without burdensome strings or mandating billing system requirements.”

And it’s the same for recovery housing, she said. “Push National Addiction Recovery Residence accreditation and let that be enough to help these houses get up and running.”

Crews said it’s critical to have services available immediately. “It takes guts and courage to ask for help,” she said. “When you are turned away, it is devastating.”

Higher reimbursement

Eric Spofford (left) is founder and CEO of Salem-based Granite Recovery Centers, which has five facilities in New Hampshire that provide the full range of services from medical detox to sober living.

Eric Spofford (left) is founder and CEO of Salem-based Granite Recovery Centers, which has five facilities in New Hampshire that provide the full range of services from medical detox to sober living.

Spofford is a recovering heroin addict; he’ll celebrate 11 years of sobriety in December.

He said one needed fix is an increase in Medicaid reimbursement rates for inpatient residential treatment, currently $162 a day. He said that is a fraction of what private insurance will reimburse for such treatment, and doesn’t cover his operating costs.

Merritt from New Futures said reimbursement rates for substance use disorder services are “chronically low, which makes it really difficult to attract clinicians to serve this population.”

“An incentive in the form of enhanced reimbursement would make a world of difference,” she said.

And Freeman from N.H. Providers Association proposes the state adopt loan forgiveness programs for young people who go into the treatment field, especially in underserved areas where they’re needed.

If Donna Marston could ask one thing of the President about opioid addiction, she said, “It would be to educate people that this is a brain disease.”

“They’re good people who are sick,” she said. “They’ve got a hole in their soul and they’re looking to fill it. And they fill it with drugs.”

Marston said she’s one of the “lucky ones.”

Her son has been in recovery for more than 9 years; he has a “beautiful wife,” she said. And their first child, a son, was born on Friday.

“So blessings come out of this nightmare,” she said.

Full article can be found here: http://www.unionleader.com/social-issues/NH-speaks-How-to-win-the-opioid-fight-10292017

Job Posting Part Time – Triangle Club Dover

The Triangle Club is hiring a part-time woman to be an Associate Recovery Coordinator with at least 6 months of continuous sobriety. We’re looking for a start date of December 1. Download Job Description Associate Coordinator Triangle Club

Associate Recovery CoordinatorTriangle Club – Dover, NH 03821 |

Part-time (up to 20 hours per week)

Club hours of operation are 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. M-F and 10-3 Sat/Sun. We are seeking individuals who can provide evening and weekend coverage. Additional hours will be on an as needed basis.

Essential Position Objectives

The Associate Coordinator of the Triangle Club will work under the direct leadership of the Primary Coordinator.

Position Qualifications:

- Extensive and active experience with 12-Step meetings.

- Working knowledge of a variety of addiction recovery modalities and the ability to oversee the successful implementation of all in-house recovery efforts.

- Ability to work a flexible schedule including evenings and weekends.

- Maintains the confidentiality of sensitive information.

- Superior phone and people skills.

- At least 1 year of continuous sobriety

PERFORMANCE GOALS

- Be a continual presence in the facility and be available to answer all phone calls.

- Deal with patrons in a compassionate yet professional manner at all times.

- Oversee and maintain when necessary, a level of cleanliness of the facility, through light but regular cleaning and through the engagement of volunteers.

- Take direction at all times from primary coordinator.

- Complete all tasks as assigned.

Interested individuals should contact Mark Lefebvre (onekaway@yahoo.com, 603-502-8900) for more details

Harbor Homes Nashua Hiring Peer Support Workers

Harbor Homes (Nashua) is hiring. It’s the Mobile Crisis Response Team and a 24/7 program, which has openings in all shifts. A high school diploma and background in some human service-related field is required, but other than that each peer support worker is trained within their first 6 months of being hired within the mental health side of peer recovery work. If you have had students in the past who may be interested, they can go online http://harborhomes.org/careers/ and follow the directions to apply with HR. They can also email a resume to my clinical director, Rob Sibley at r.sibley@nhpartnership.org.